Sud De France: History of Winemaking

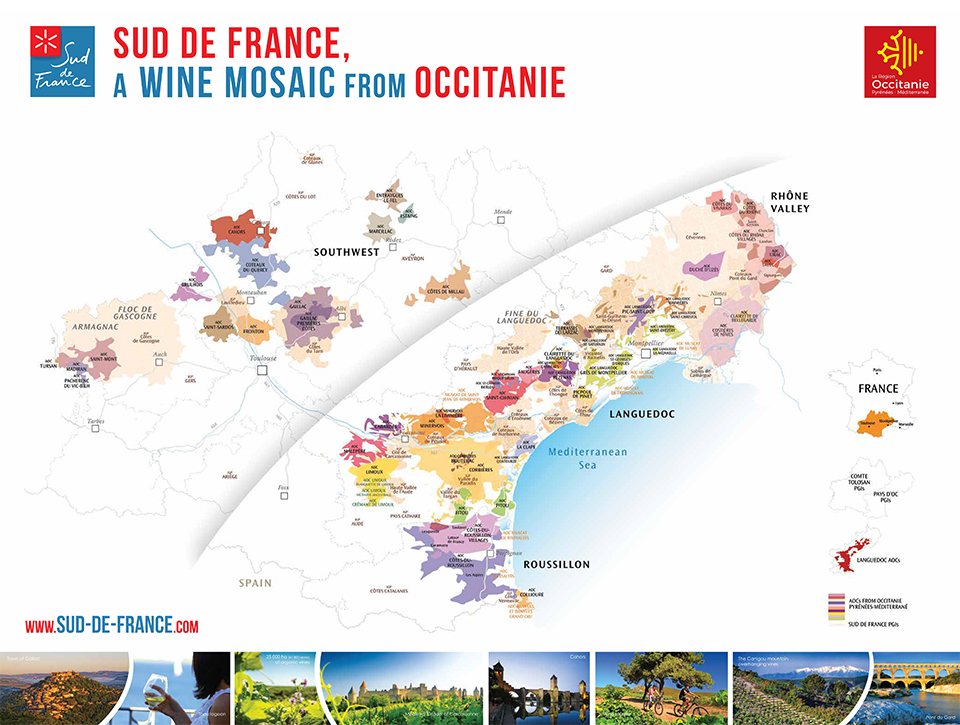

My list of recommended wine brands did not include the Sud De France wine brand; in fact, it was not even on the list. Sud De France showcases the richness and beauty of the area, which is situated in the middle of the Midi-Pyrenees and Languedoc-Roussillon. Occitanie is the region’s new name, chosen due to the languages’ historical importance and the Occitan language itself.

The Occitanie is a region that resembles the territory ruled by the Counts of Toulouse in the 12th and 13th centuries, and the Occitan cross, which they used, is now a well-known cultural icon.

Occitanie became official on June 24, 2016, and includes the following locales and population:

- Toulouse (479,553)

- Montpellier (285,121)

- Nîmes (150,610)

- Perpignan (120,158)

- Béziers (77,177)

- Montauban (60,810)

- Narbonne (54,700)

- Albi (50,759)

- Carcassonne (47,365)

The area is located between two mountain ranges, the Massif Central in the north, and Pyrenean foothills in the south, and between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean.

Most of the wines in the Languedoc-Roussillon area are blends of important traditional red varieties including Carignan, Cinsault, Grenache Noir and Mourvedre. Current plantings include Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah. The most important white varieties are Grenache Blanc, Marsanne, Rousanne Viognier and Ugni Blanc with a growing interest in Chardonnay.

Although this portion of France has notable wine achievements, its history is obscure, except for historians and academics who focus on the economics and political foundations of the wine industry.

Research suggests that the Languedoc-Roussillon region was first settled by the Greeks who planted vineyards in this area in the 5th century BC. From the 4th through the 19th century, Languedoc was noted for producing high-quality wines but this changed with the arrival of the industrial age when production pivoted toward le gros rouge, mass produced cheap red table wine used to satisfy the growing workforce. Languedoc became renowned for producing vast quantities of poor plonk that was served in massive quantities to the French troops during WWI. Fortunately, this focus has passed into history, and the area now produces quality wines. Currently local winemakers produce wines from Bordeaux style reds to Provence inspired roses.

Years ago, I had the good fortune to review this part of the planet and was introduced to the biodynamic approach to grape growing and winemaking from the perspective of Gerard Bertrand. What I did not know, was the tumultuous history of the region and how the actions and activities of the early 20th century wine industry participants and the French government created the foundation for the current state of the wine industry in the Occitanie region.

We do not usually think of people in the wine industry as being revolutionaries and certainly not militant; however, in 1907 French winegrowers from Languedoc-Roussillon led a mass protest estimated to number approximately 600,000 – 800,000 people. In 1908 lower Languedoc had a population of one million people, so, one of every two Languedocans demonstrated, paralyzing the region and challenging the state.

Why were the French “up in arms?” They were threatened by wines imported from the French colony of Algeria through the port of Sete, and by chaptalization (adding sugar before fermentation to increase alcohol content). Members of the wine industry revolted, and demonstrations included all levels of the industry – from grape growers and farm workers to estate owners and winemakers. The wine industry had not experienced such a crisis since the outbreak of phylloxera (1870-1880). The situation was dire: winemakers could not sell their product leading to high unemployment and everyone feared that things would get worse.

At the time, the French government thought that importing Algerian wine was a good idea as a way to address the decline in French wine production which was a result of phylloxera. From 1875 to 1889, one-third of the total French vine area was destroyed by this root eating insect and French wine production declined by approximately 70 percent.

As phylloxera spread, many French winegrowers migrated to Algeria and introduced their technology and expertise to the region where grapes had been growing since the first millennium BC; however, centuries of Muslim rule created a local population that did not consume alcohol. The good news? Wine consumption in France remained the same! In a shortsighted attempt to deal with the shortage issue, the French government encouraged wine production in its Algerian colony while limiting imports from Spain or Italy.

When the phylloxera crisis was resolved by grafting American root stock onto French wines, the French wine industry started to recover and slowly production returned to a pre-crises level of 65 million hectoliters. However, the Algerian wines continued to flood the market at a lower price (decline of over 60 percent over 25-year period), negatively impacting French producers.

Protests

French wine producers wanted limits set on imported wine and started to demonstrate through street protests and violence (actions directes) including mutinies, pillage, and the burning of public buildings. in June 9, 1907, the Revolte (Grande Revolte, Revolt of the Languedoc winegrowers; also known as the Paupers Revolt of the Midi) included tax strikes, violence, and the defection of many army regiments creating an atmosphere of crisis that was repressed by the government of George Clemenceau.

Although the uprising was regional, the National Assembly feared that this southern movement was actually an attack on the French Republic. In response to the demonstrations, the French government increased tariffs on wine imports from Italy and Spain which was another mistake as it further increased the consumption of tariff-free imports from Algeria.

Once again, French producers (including Bordeaux, Champagne and Burgundy) went after the government “encouraging” them to stop the inflow of Algerian wines as they wanted to protect their own “high quality wine” markets. They forced the introduction of new legislation, supporting the political representatives from the regions that agreed with their position. This fear proved to be an illusion and the movement ultimately ended in compromise, disappointment and what appeared to be a victory for the central state.

The port of Sete acted as a catalyst for the crisis. This city was the center of a large production area and it increased the risk of overproduction by encouraging the use of Aramon grapes from large vineyards – creating volume. Algerian wines and production increased from 500,000,000 liters in 1900 to 800,000,0000 in 1904. The increased production and the availability of fake wines and blends from Algerian wines saturated the consumer market and imports increased in 1907 swelling the imbalance between supply and demand causing the decline in price and ultimately sparking an economic crisis.

In 1905 the French government passed a law on “frauds and falsifications,” laying the groundwork for the production of a “natural” wine. Article 431 required that wine sold had to clearly state the wine’s origin to avoid, “misleading commercial practices,” and explicitly stated that the law also applied to Algeria. Other laws to protect the wine producers introduced a specific link between the “quality” of the wine, the region where it was produced (terroir), and the traditional method of production, establishing the regional boundaries of Bordeaux, Cognac, Armagnac and Champagne (1908-1912) and referred as appellations.

Unfortunately, the wine producers in Southern France were unable to benefit from these laws although the lobbied against Algerian wines as well. The government was unwilling to impose tariffs on Algerian wines for it would have had an adverse effect on the interests of French citizens overseas and was inconsistent with the integration of Algeria as a French territory.

Ultimately, the new laws had little impact on the French wine markets and Algerian wines continued to flood the French markets and the Algerian wine production increased, assisted by a law allowing agriculture credit banks to provide medium and long-term loans to wine producers. European settlers in Algeria borrowed substantial amounts of capital and continued to expand their vineyards and production. It was not until the French government stopped all non-French wine from being used in blends (adopted by the rest of Europe in 1970) that there was a decline in Algerian wine production. In addition, from 1888 to 1893, Midi winemakers launched a full-scale press campaign against Algerian wines claiming that the Algerian wines being mixed with wines from Bordeaux were poisoned. Oenologists were unable to substantiate the claim; however, the rumors continued until the 1890s.

The government of Algeria turned to the Soviet Union as a possible market and they established a 7-year contract for 5 million hectoliters of wine annually – but the price was too cheap for Algerian winemakers to make a profit; without export markets available, production collapsed. There was no domestic market because Algeria was and continues to be primarily a Muslin country.

Although the laws were motived by the situation with Algerian wine imports and low prices, the impact has been long. In 1919, a law specified that if an appellation was used by unauthorized producers, legal proceedings could be initiated against them. In 1927, a law placed restrictions on grape varieties and methods of viticulture used for appellation wines. In 1935, Appellations d’Origine Controllees (AOC) restricted production not only to specific regional origins but also to specific production criteria including grape variety, minimum alcohol content, and maximum vineyard yields. This law formed the basis of the AOC and DOC regulations which are significant in the European Union (EU) wine markets.

© Dr. Elinor Garely. This copyright article, including photos, may not be reproduced without written permission from the author.